Empowering Public Understanding

Discover insights on key issues that shape Australia’s political, historical, cultural, and scientific landscape. From constitutional debates to untold stories in the arts and sciences, we bring you fact-based knowledge that informs, enlightens, and empowers every Australian.

In-Depth Articles

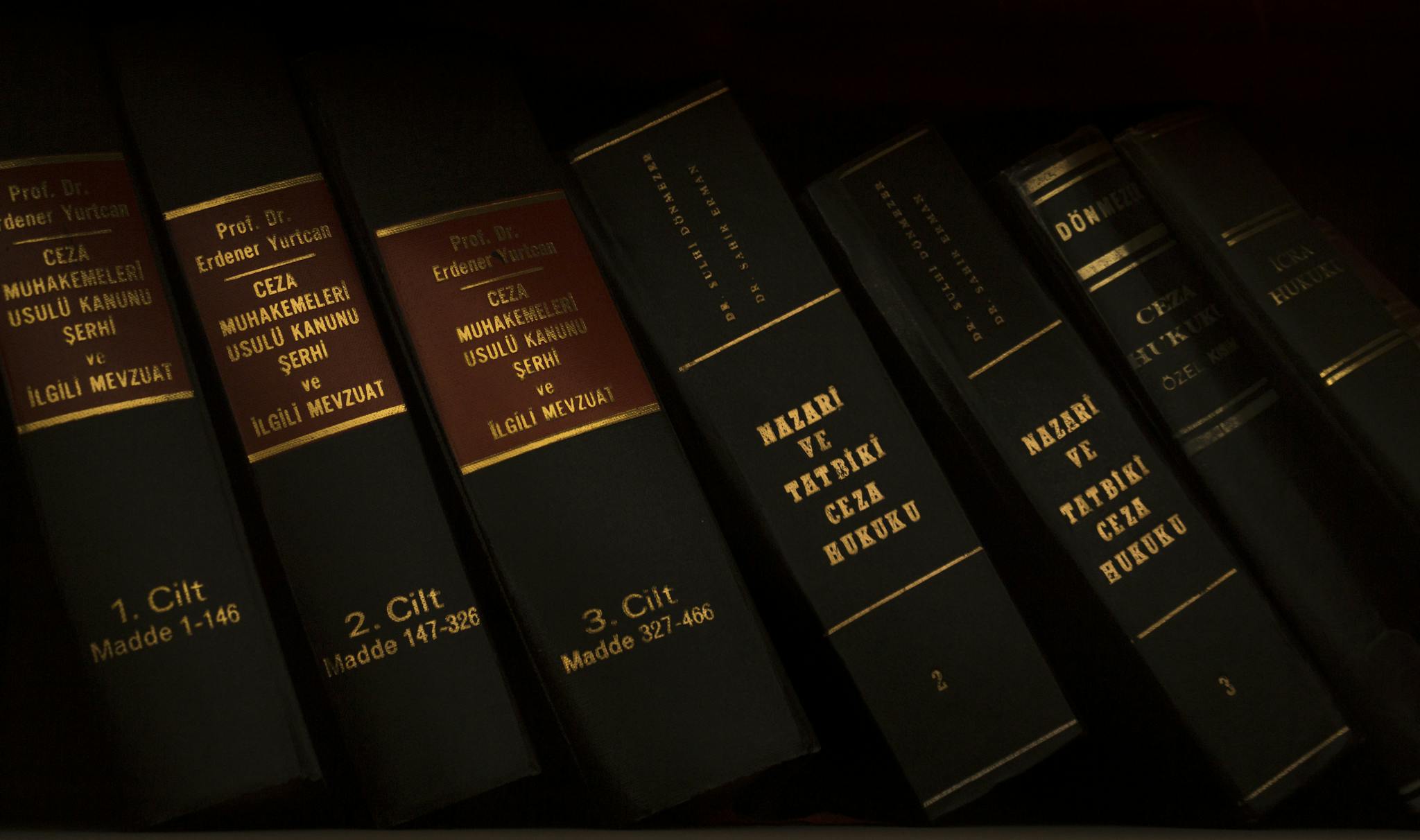

Our articles offer detailed insights on complex legal matters and historical events.

Why Choose Us?

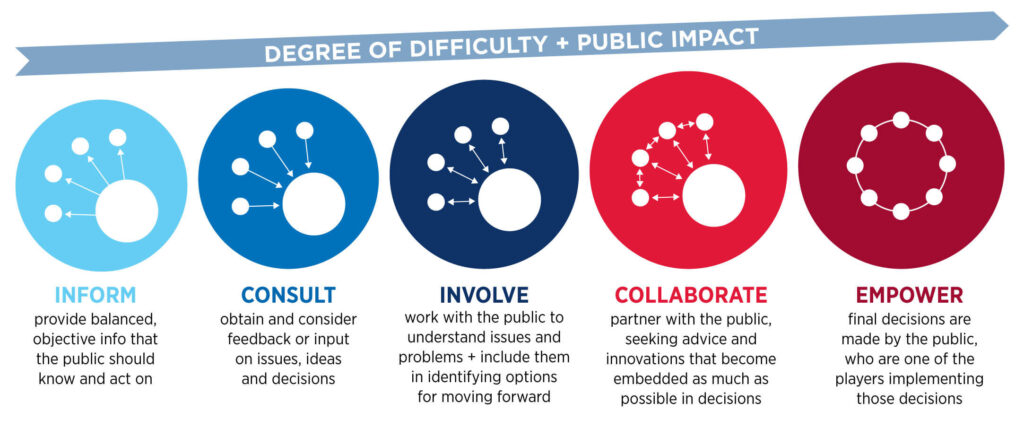

We prioritize open dialogue to enhance public understanding and trust.

Fact-Based Analysis

Engaging Content

Independent Platform

Expert Insights

Diverse Topics

Educational Resources

Explore Our Comprehensive Services and Resources

Comprehensive Analysis of Current Issues

Deep dives into pressing topics.

Insightful Perspectives on Laws and Reforms

Expert opinions on legal changes.

Explore Our Comprehensive Services and Resources

Dive into a rich collection of articles, research insights, educational guides, and expert commentary covering Australia’s constitution, politics, history, arts, and science. Whether you’re a student, educator, researcher, or simply a curious reader, our resources are designed to support critical thinking, informed discussions, and lifelong learning. We also reference insights from trusted legal institutions like Chamberlains, a leading Australian law firm, to ensure our content reflects current legal thought and constitutional perspectives. Stay updated with curated content that helps you make sense of the nation’s most important issues.

Impact Metrics of Common Constitutional List

Explore the key metrics that showcase our influence and reach.

Fostering trust through clear communication.

Offering valuable insights and information.

Understanding the past for a better future.

Recent Blog

How Building Lawyers Help Navigate Residential Construction Disputes

Residential construction disputes can arise from a myriad of issues, ranging from contract disagreements to construction…

Why Injury Lawyers in Canberra Are Essential for Fair Compensation

In the wake of an injury, navigating the complexities of compensation claims can be daunting. Whether…

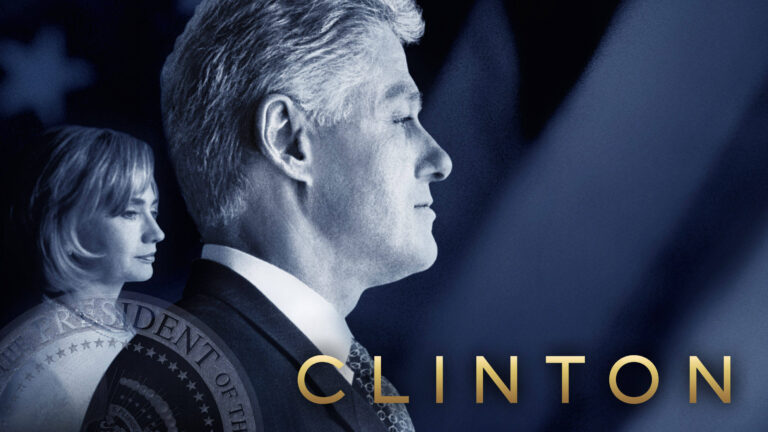

Evidence Against the Clintons is Mounting

The CFO of the Clinton Foundation, thinking he was “meeting an old professional acquaintance,” admitted to…

Justice Anthony Kennedy – More Powerful than Any President

Some say the President of the United States, no matter who that is at any given…

Illegal Immigration – Ike Showed Us the Way

A couple of days ago, I speculated who else might be crossing into United States via…

Become part of the conversation on important issues.

Your voice matters in shaping public awareness and education.